Earths Natural Thermostat – Her Ocean Pastures

Earths natural thermostat found: Dust in the wind made more abundant in the dire stages of global warming will lead to global cooling (if we wait for centuries).

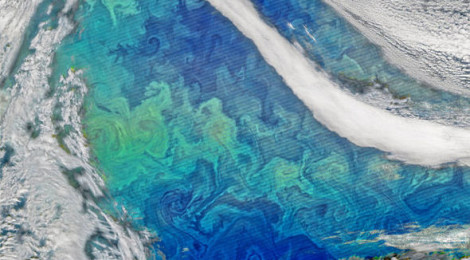

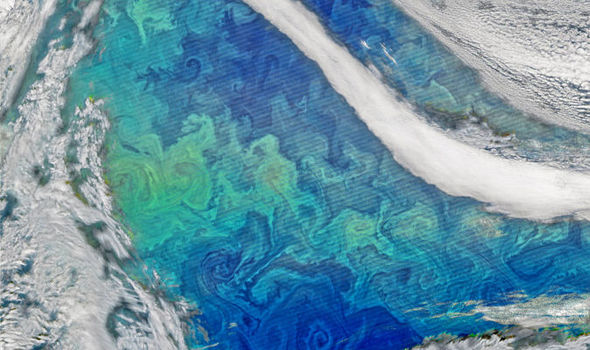

Plankton blooms as seen from space by NASA may appear as art but they also show the way to reduce CO2 and global warming.

NASA’s Earth Observatory Plankton Bloom in North Atlantic Fall 2015

Each spring and summer (and sometimes the fall) the waters of the world’s seven seas host huge natural blooms of phytoplankton—microscopic, floating plants called phytoplankton. These tiny plants are important for managing the Earth’s CO2 as they consume the CO2 in their process of photosynthesis. They also dramatically help to produced clouds which reflect sunlight away from the planet. The photosynthesis, cloud production, and their range covering 71% of this blue planet make these ocean pastures earths natural thermostat for controlling CO2, climate change, and global warming.

“A lot of what we don’t know about ocean ecology has to do with the difficulty of studying the ocean,” said Norman Kuring, an ocean scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, “whether it be from a storm-tossed ship or from a cloud-obstructed satellite.”

On September 23, 2015, the skies were mostly clear for the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP to acquire this view of a bloom in the North Atlantic. The image was composed with data from the red, green, and blue bands from VIIRS, in addition to chlorophyll data. A series of computer processing steps (think photoshop) were used to highlight color differences and bring out the bloom’s more subtle features. (The process also accentuates stripes, artifacts from the detectors, that can be seen throughout the image.)

“The image does a beautiful job of showing the close link between ocean physics and biology,” said Michael Behrenfeld, a phytoplankton ecologist at Oregon State University. “The features that jump out so clearly represent the influence of ocean eddies and physical stirring on the concentration of phytoplankton pigments and, possibly, colored dissolved organic matter.”

Six weeks after this image was acquired, researchers were in this area with NASA’s North Atlantic Aerosols and Marine Ecosystems Study (NAAMES). The study aims to make ship and aircraft-based measurements that, when combined with satellite and ocean sensor data, will help clarify the annual cycles of ocean plankton and their relationship with atmospheric aerosols. The first field campaign of the five-year study began November 6, 2015, and concluded December 1.

Researchers on the ship-based part of the study ran into some wicked November weather. Christien Laber, a doctoral student at Rutgers University, captured this photograph during a storm on November 19, when the research vessel Atlantis was off of the Newfoundland Shelf. Some research had to be put on hold for the day, though some continued through the storm.

Getting to such ocean pastures requires determination as can be seen in this image from a research ship sent to collect samples of the blooming ocean pasture 19 Nov. 2015

“We have a ton of analyses to do to fully determine all the cool things that were going on out there,” said Behrenfeld, the principal investigator for NAAMES. “What I do know is that the ship data transected through a range of phytoplankton concentrations, and that these features were associated with ocean physical features.” Moreover, the plankton observed were diverse and in good health, “as if they are ready to bloom given any chance.”

As expected, the number of plankton in the water in November was very low. Behrenfeld explained: “It is likely that these low concentrations have an impact on predator-prey relationships between phytoplankton and the zooplankton that eat them.”

The effect of plankton, however, can sometimes reach beyond the sea and into the atmosphere. Rich Moore, a researcher at NASA’s Langley Research Center and deputy project scientist for NAAMES, explained that biological organisms release organic molecules into their surrounding seawater. This seawater, organic particles and all, can then be lofted into the air as sea spray.

“These biologically-driven aerosol influences have been detected as far away as coastal monitoring stations in Ireland,” Moore said. “However, we have much less information about what is going on out in middle of the ocean. NAAMES will attempt to fill this important scientific gap by studying the link between the bloom, any changes in the overlying atmospheric aerosols, and how these changes may then go on to affect clouds and regional climate.”

The next NAAMES campaign will begin in May 2016. “This is going to be the climax of the bloom,” Moore said “and will serve as an exciting foil to the minimum that we just characterized in November.”

Can we afford to wait for the global warming end of days to employ our oceans to save us from our CO2

Nature has infinite patience and we puny humans don’t really matter much in the billion year time frame that Nature lives in. She grew and evolved many forms of dominant life on her blue planet over the eons of time. If we send our species to an early extinction Mother Nature might shed a tear but we won’t be here to see it fall. It is up to us to use the tools Mother Nature provides us to manage our time on this blue planet. Waiting for our CO2 forced ecological chaos to be fixed by Nature is not exactly viable as we will be long extinct before nature employs her fix.

We can however make a voluntary advance payment to Nature on our lease of the planet. We simply need to give back to the oceans the dust we have been denying them and forcing the dramatic reduction of ocean plant life. Doing so will require some very few of us braving the stormy seas to deliver the dusty payment but it’s very doable, I should know I have proven it can be done in my 2012 50,000 sq. km restoration of a desolate ocean pasture in the N. Pacific.

By doing this each year in all of the world’s seven seas billions of tonnes of our noxious CO2 will be repurposed by Mother Nature’s plankton blooms into new ocean life. The cost is trivial mere millions of dollars each year until the end of our fossil fuel age. Compare this cost to manage the lions share of global anthropogenic CO2 with the more than a trillion dollars per year now endorsed by the Paris Accord to manage CO2 by political, societal, and industrial upheaval.

IT JUST WORKS!

My 2012 ocean pasture replenishment and restoration work in the NE Pacific returned the ocean to life as seen in the largest catch of salmon in all of history in Alaska the next year.

Here’s my prescription to begin.

-

References and Related Reading

- John Martin ocean dust guru On the shoulders of Giants

- NASA Earth (2015, November 19) Five-Year NASA Study to Look at the Immense Influence of Petite Plankton.

- NASA Earth Data (2015) Ocean Color Web.

- NASA’s Langley Research Center (2015) NAAMES.

- O’Dowd, C. et al., (2004, October 7) Biogenically driven organic contribution to marine aerosol. Nature, 431 (2004), 676-680.

NASA image by Norman Kuring, using VIIRS data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Suomi NPP is the result of a partnership between NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Department of Defense. Photograph by Christien Laber, Rutgers University. Caption by Kathryn Hansen.

- Instrument(s):

- Photograph

- Suomi NPP – VIIRS